Seeing People: A Conversation With the Artist Annu Palakunnathu Matthew

Shilpi Suneja

We are living in times when appearances contribute more than their fair share of vocabulary to a person’s story. We mine every physical attribute—the color of skin, the color of hair, the style of hair, the donning or eschewing of a contested piece of clothing (a hijab, a trench coat, a swim suit)—to glean information about a person’s level of commitment to a religion, to a nation, a race, a class, a caste, a political preference, a musical movement, a sexual orientation, a series of historical privileges or baggage, and how all of this aligns with our own ideas of freedom and justice. Of course, much of what we discern from these attributes is pure assumption, likely only stereotypes.

The dictionary defines a stereotype as “a conventional image” of a person or a society. Stereotypes form on the basis of how we come to know and classify people and their beliefs from around the world. We have molds for everyone. The media—music videos, films, games, news, even books—create these molds, but we play a part in internalizing them, in accepting them without question.

Molds can be dangerous. Even before a person has had the chance to open her mouth, our minds form an opinion. This happens repeatedly. It happened in the crowded subway in Portland when two men were stabbed to death defending two women of “Muslim appearance.” It happens each time a white cop encounters a black man or woman inside or outside a moving vehicle.

How do we break these molds? How do we unlearn what the media spends billions of dollars teaching us? This task invariably falls on the artist. A good artist can reorder popular images in such a way that we feel disoriented and uncomfortable, and eventually, we arrive to a new understanding of ourselves.

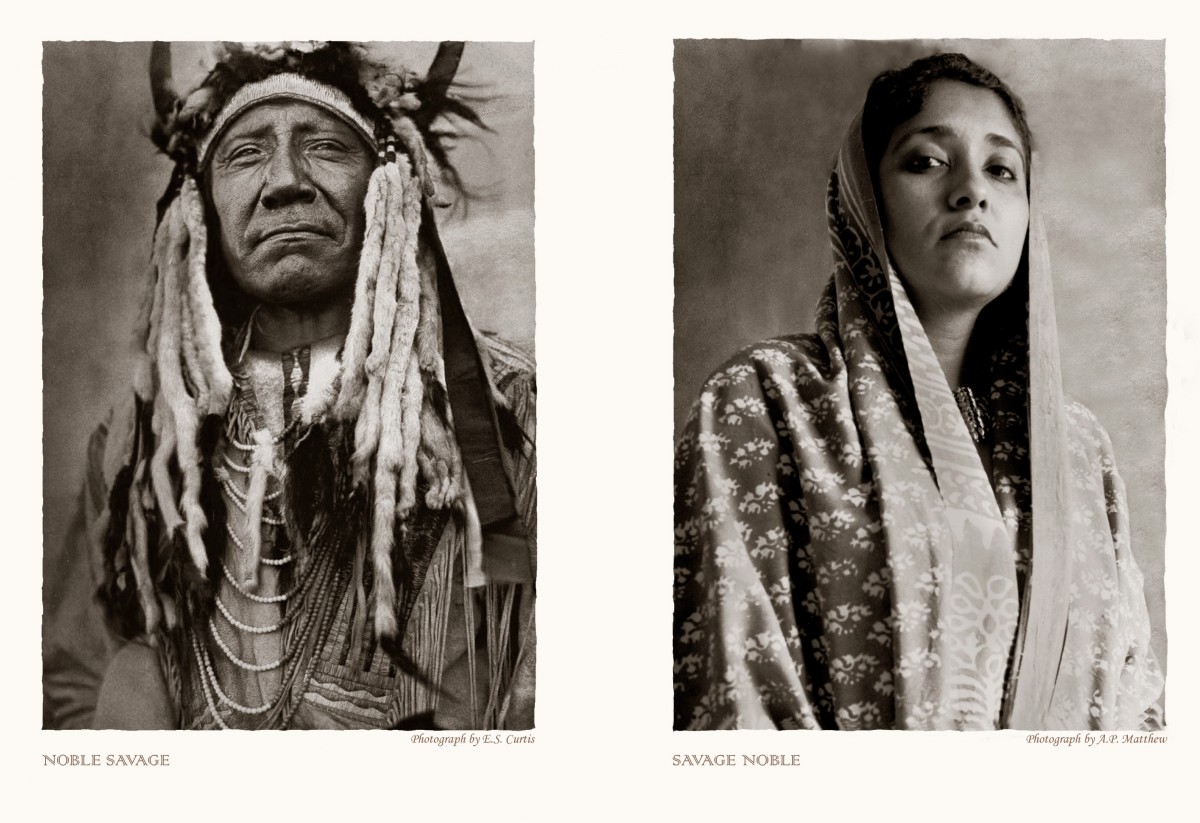

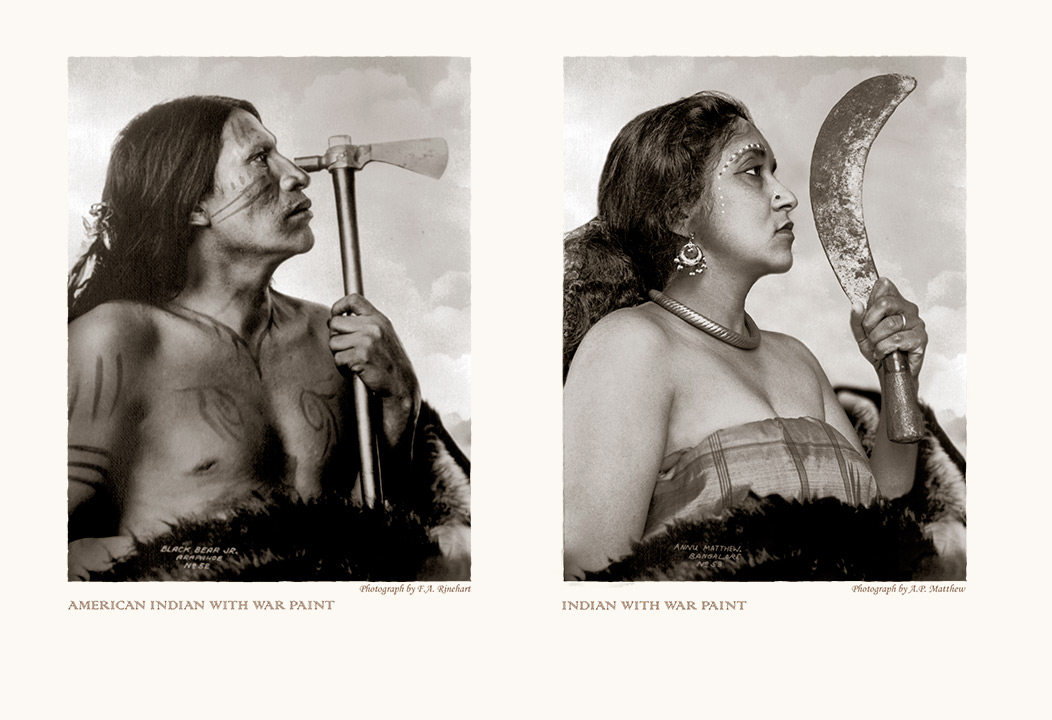

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew’s photographs do exactly this kind of work of defamiliarizing the “conventional image” of the outsider, the immigrant, the native, and the settler. Having lived in India, the United Kingdom, and the United States and identifying as an immigrant in the US, she puts her own experiences to use in her art. In her collection An Indian from India for example, she humorously juxtaposes photos of herself in outrageously stereotypical “Indian” clothing alongside 19th-century photos of Native Americans in equally outrageous costumes of war paint, head gear, and scythe, costumes that the original photographers thought were typical to the original Americans. The collection is her artistic response to the question we all get asked: “Where are you really from?”

from An Indian from India

Her work, which I had the privilege to see at a discussion in a friend’s house, excavates her subjects from conventional molds and restores to them their histories of struggle. Take for example the collection To Majority Minority. In this series, within the framework of an old photo, men and women dissolve, disappear, and reappear as their older selves. The background—a parked vehicle, an ancient armchair—remains the same, but the people age, or in some cases, completely disappear. In one photo, a young girl dissolves, then reappears as an old woman; another young woman, her daughter, appears beside her; a baby appears on the second woman’s arm; the new mother ages; the grandmother, the original woman in the photograph, slowly disappears.

At the gathering in my friend’s house, these animations had a powerful effect on the people in the room. It was as though something tragic was happening to these families, and all we could do was watch. Within the timespan of a few seconds, history was quietly unfolding. Annu’s photos captured, even hastened the process of aging and dying, things that take years to pass. That “haste” becomes a metaphor for the rapidity of violence, particularly the kind of violence that happens in conditions of war and forced migrations. In the instances of the Holocaust and the Partition of India, lives—millions of them—were lost instantly. There was no transition, not for the individuals dying and not for their families who most likely received the tragic news in one-line telegraphs, in government lists, by word of mouth and rumors, or, perhaps not at all. Annu’s animated photographs captured the spectacle of death, and in the simple and elegant trope of the disappearing individuals gave voice to the unspeakable violence of loss.

To Majority Minority—Thuan from Annu Palakunnathu Matthew on Vimeo.

This is what is remarkable about Annu’s work—she does so much with photographs and with simple animations such as the ones described above; she earns so much empathy and pathos for her subjects and for the themes and phenomena she explores.

So much of her work is about memory as with the animated family photographs and the series of photos on India. This is imperative work because, in this age of Twitter and Instagram, we tend to forget so easily. We become callous to what is not immediate. The stories of our mothers and the struggles of our grandmothers all seem like boring history lessons. In working with family photos, Annu attempts to document these historical, “dated” emotions we do not feel, but our forbearers did. Her photographs succeed not only in capturing the passing of time, but also in slowing down time. All good art sets itself for exactly this enterprise—to slow down time for the reader/viewer.

Long before the discussion ended, I knew I had to interview Annu. She is an artist whose work on immigration, migration, and the consequences of war we most need at times such as these.

Shilpi Suneja: You seem to be fascinated by the ideas of transitions and transformations—the process of aging, the transformation of personalities of call center workers, the dilemma of migration. What motivates you as an artist to capture change, to capture transitions? Do transitions tell a story? I say this because, as a writer, I too am tasked to capture transitions—the change in a person, in a family, in a house. Even if the change is the acquisition of new knowledge, say, the learning of a family secret, the individual does not remain the same. Your photographs achieve a similar effect, especially the ones in ReGeneration, To Minority Majority, and Open Wound. They each tell a story about an individual’s and, by extension, a family’s transformation over time, the change wrought by large, external forces of war, displacement, and migration. Your animations recreate these transformations. I find this resonance between your life as an immigrant and your work to be very beautiful, very synergetic, very interesting. Can you comment on this?

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew: A photographer whose work has influenced me is Duane Michals, and this quote in particular resonated with me and which, I think, will partially answer your question: “I think photographs should be provocative and not tell you what you already know. It takes no great powers or magic to reproduce somebody's face in a photograph. The magic is in seeing people in new ways.” Over the years my work has built on existing imagery (such as in An Indian from India and Open Wound) or familiar commercial processes (like using the lenticular print in The Virtual Immigrant) to draw the viewer in. The work has gone from sequences to transitions to photo animations. I have been interested in expanding the single photographic image to engage the viewer to explore re-looking at cultural histories, identity, and memory. The transformations in ReGeneration, To Minority Majority, and Open Wound engage the viewer to learn the larger stories of these families. The photo animations remind me of the magic of the darkroom where the image slowly emerges in the tray.

from Memories of India

There is always a resonance between my life and the work that I do. As my husband flippantly likes to say, my work is about me, me, me! I would prefer to say that as an artist, I raise socio/political questions through known imagery to prompt audiences to rethink their notions and assumptions. Ok that is getting a little academic! But yes, I have to connect to the concept for a project to emerge.

SS: You worked on a collection, Memories of India, quite early in your career. I understand that you undertook this project after you had moved to the US to study photography. You were already an immigrant. The loss of home prompted you to take a camera and travel in India to capture the sights through the nostalgic eyes of one who has lost India, lost her home. And yet, in this whole collection we remain outside a “home.” You show us beautiful sights—men at work, a woman stepping into a river, an elephant bathing—but still we remain outside of a home. Even in Fabricated Memories, a home or even a homely place—a couch, a bed, a kitchen—is missing. There are cars, there are boats, there is a merry-go-round with clowns—all public spaces, not private. Did your idea of home change once you left India? Was this an avoidance of the intimate? Or perhaps a new articulation of the idea of home?

APM: As I was born in England, spent my teenage years in India, and now live in the United States, I see myself as a transnational artist who belongs and relates to multiple cultures. I am simultaneously an insider and an outsider. The Memories of India portfolio reflects a perspective that understands the culture but includes a distance that doesn’t completely belong. There are no faces—just silhouettes. Memories of India is more a homage to my cultural homeland rather than showing specific scenes of where I lived and went to school. Again I want to engage the viewer without making it literal.

SS: That is beautiful! I can quite see in the photos of Memories of India how you appear both as an insider and outsider. Not completely belonging to one culture frees you to explore the aesthetics of other cultures. What artistic traditions have influenced you? Who are the artists whose work speaks most to you? One article compared your series Bollywood Satirized to Guerrilla Girls. Your An Indian from India satirizes the photos of early American photographers. Could you speak about your aesthetics?

APM: I choose my aesthetic based on the concept I want to communicate. This has varied over the years and, as a result, compared to other artists, I don’t have a particular “look.” My background has obviously influenced me, including my undergraduate work in mathematics and my aptitude with computers. The digital toolbox offers endless possibilities that I continue to explore so that my technique dovetails with the idea that I want to convey. The artists that speak to me the most are ones who deal with transition/transformation. For example James Turrell, Duane Michals, Hiroshi Sugimoto (empty theaters), and Anish Kapoor. Unfortunately they are all men! Shirin Neshat was an early influence.

Bollywood Satirized was created when I was an angry young Indian woman! I am not sure I could do that kind of work now even though I am glad I did it.

SS: In your discussion you mentioned using a Holga for Memories of India, a camera that helped you be less conspicuous and allowed you a degree of anonymity. Has the iPhone made it easier to take photos surreptitiously? Do you experiment with the iPhone camera? I wonder if you can speak more about your need to be inconspicuous. I feel that in times like these artists are asked to do the opposite—to be conspicuous, to lend their voice and their artistic labors to a cause, and visibly so. But one also feels the need to disappear and produce good art from a place of anonymity, invisibility. Can you speak about this double bind?

APM: Memories of India is the only unmanipulated photography project that I have done. It accesses my more intuitive side where I am reacting to light, gesture, and memory. The Holga does make me inconspicuous, but the people around me are aware that I am taking photographs. As I may shoot a few rolls of film at one location, they get fed up watching me after five minutes, which allows me to be able to watch the ballet of life happen around me to create an image that reflects it.

Reading the quote below by Susan Sontag in On Photography influenced my approach to my use of the self-portrait in An Indian from India and to a more collaborative approach in Open Wound, To Majority Minority, and ReGeneration.

“There is something predatory in the act of taking a picture. To photograph people is to violate them by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed.”

I too have switched to using my iPhone, and I also enjoy showing people my images afterwards and conversing about them. Digital has helped reduce the imbalance in power between the photographer and subject, though I rarely photograph people who are publicly recognizable.

In my larger work, I think I “disappear” when I am doing the long and tedious post-production work.

SS: Indeed! Your work doesn’t come anywhere close to being predatory in the way Sontag refers to it. By inserting yourself into the photograph (in An Indian from India) or by working with families to recreate the history-laden photos of To Majority Minority, your work presents much of your subjects and their voices (quite literally!) without an egregious amount of artistic filter.

I am curious how you begin a project. Do you begin first with themes and ideas? What is the seed that eventually grows into a tree?

APM: I have a variety of ideas that don’t lead anywhere. As I mentioned before, an idea has to resonate with my own experiences. I usually start with a concept and then explore visual approaches. Each project can take years. Sometimes just deciding on the final presentation can take years (as with Fabricated Memories)!

SS: You came to work on the Partition of India tangentially, by way of the Jewish Holocaust. Can you speak about how it has been for you to create work on Partition? How has it helped you to grow as an artist?

Open Wound—Kohli from Annu Palakunnathu Matthew on Vimeo.

APM: ReGeneration, which started in India, led me to continue the project in Vietnam and Israel and the Palestinian Territories to compare family photographs across cultures. When I photographed a Holocaust survivor, I was surprised at myself for not realizing the obvious—that every family has a story that we can’t tell from the family photograph. I was also surprised that when talking to my high school classmates, we hadn’t learned about Partition in India. Consequently, its history and implications were absent from our viewing contemporary politics.

The more I read about Partition’s history, the more disturbed I was. I have been reading Nisid Hajari’s Midnight Furies for the last three years. Every time I pick it up I have to start from the beginning as I have blocked out the horrifying evidence that I previously read. In 2012, I had turned my lens to my current experience of living in the United States. But with my new knowledge I was sucked back to my cultural homeland. Working on the Partition project made me realize the responsibility that I have as an artist to not break the trust of my subjects. In the last five years, Indian, Pakistani,and Bangladeshi families have let me into their homes and trusted me with their most personal stories. The powerfully disturbing, emotional rollercoaster journey I have been on has inevitably affected me as a person and an artist.

SS: Another one of your projects, The Virtual Immigrant, documents call center workers in India taking on new personas during their workdays (really, nights) in order to sound more “authentically” American to American callers. It is fascinating that by just taking on American names, changing their accents and learning about American culture (while never visiting America) these “virtual immigrants” can reflect upon certain very deep psychological traits of Americans and the American dream.

One woman you interview says, “In America you have to ask for things if you want them, not like here.” She went on to say that she would do better in a society such as America’s. I found this to be a very telling revelation. This schizophrenia of becoming an American by night and turning back into an Indian by day produces interesting consequences such as not fitting into your own family, feeling out of place in your own country, your own home. In fact, this schizophrenia is a continuation of colonization.

One of the methods by which English Raj lasted so long in India was by the colonization of native minds, a process that produced Brown Sahibs or native Englishmen—people who lived in India but loved England, English language, English literature, English clothes, English law, English economic models, English industrialization. In some ways, those of us who speak English are the products of this phenomenon. We now call ourselves anglophiles, a word that sounds like a euphemism but captures the self-hate that colonization engendered.

True story: The tech companies where I worked each had a “Bangalore Team”—people who lived in Bangalore but worked for American companies. The “Bangalore Team” worked on the US schedule—8 AM to 7 PM Eastern Standard Time, which in India is 5:30 PM to 4:30 AM. The Americans took for granted that the young men and women on the “Bangalore Team” could be called and emailed and expected to do perfect work during normal working hours, never once reflecting that it was in fact 2 AM or 4 AM in India. There was also the expectation that these young men and women would seamlessly fit into the whole baseball and beer-drinking culture of America. Dominant cultures demand that we change the very core of our beings. In some ways the disembodied voices of the call center workers in your videos capture this loss. Could you reflect a bit more on this?

The Virtual Immigrant–Identity from Annu Palakunnathu Matthew on Vimeo.

APM: The Virtual Immigrant experience does relate to what you call the colonization of the mind. You are right that we English speakers are also the products of this phenomenon. Our possible complicity is something that I am grappling with right now. But I also see the schizophrenia of “not fitting into your own family, feeling out of place in your own country” as also relating to the immigrant minority experience.

I interviewed each of the call center workers for over an hour and then condensed the audio into a ten-minute track. From listening to the hours of audio, it was obvious that being employed as a call center worker had its drawbacks, from the horrendous work hours and the schizophrenic to its advantages—being more aware of the effects of the caste system and changing gender roles. It has also allowed the job to be a stepping-stone towards more job and educational options for a diverse range of socio-economic classes. But the larger question is, at what cost?

SS: Could you tell us about what you are working on? What can we expect to see from you and where?

APM: Unusually for me I am working on a few parallel projects. In a number of interviews for Open Wound, participants have said that watching the Syrian refugee crisis on TV triggered strong memories of their own experience. Hearing this repeatedly, and in response to the recent anti-immigrant rhetoric in our current US political climate, has led to my most recent social media (Instagram and Facebook) project Refuge in Rhode Island. In collaboration with Pakistani–Puerto Rican American Aisha Manzoor, we tell the stories, through images and words, of recent Syrian refugees to Rhode Island.

I am also about to spend two weeks in Rome on a fellowship exploring the impact and role that Indians who fought for the British army in the 1940s played during the critical battle of Monte Cassino.

I have also started working on a project about the experiences of those of us who are women, minorities, and immigrants and living in this new political climate where our vision of the American ideal has been shattered.

It is too early to tell which of these will continue as a long-term project!

Images Courtesy Annu Palakunnathu Matthew and sepiaEYE, nyc.

All images and videos are copyrighted by Annu Palakunnathu Matthew and have been reproduced here by permission from annumatthew.com.