The Stories Bao Phi Tells

Simi Kang

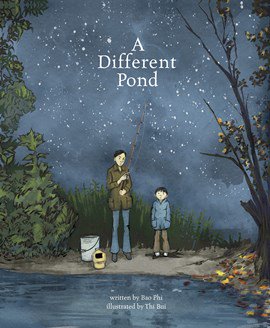

Cover design by Karl Engebretson

Cover illustration by Thi Bui

Survive long enough

and eventually

everything becomes

a revolution.

–Bao Phi, “Being Asian in America”

Well known for his spoken word poetry, Bao Phi has long articulated the violences and possibilities folded into the Asian American experience to a national audience hungry for stories about and for us. When Phi finally gave us a collection of poetry, Sông I Sing in 2011, the celebration was loud and long. Now, six years later Phi is releasing two new books within a month of each other: his second book of poetry Thousand Star Hotel (Coffee House Press), due out on the 4th of July, and his first children’s book A Different Pond (Capstone Young Readers), illustrated by Thi Bui, available August 1st.

So many of us yearn for role models, fearless storytellers to reflect the truths of our experiences. For me and countless others, Bao Phi is among these voices. I had the opportunity to speak to Phi about both texts’ lessons and themes, how writing allows him to reflect on difficult moments in the past and present, and what galvanized him to tackle a children’s book.

Where Sông I Sing felt like a love letter to Asian America—the opening poem, “For Us,” truly was—Thousand Star Hotel is much more specific to Phi's own stories. He explains that the period in which he wrote what became the book “coincided with the birth of our daughter, a breakup, and…just life. [It is also a reflection on] growing up in a working-class neighborhood and now raising a child in a working-class neighborhood, and both the wonders and the challenges of that.”

This is clearly reflected throughout the collection, where memories from childhood, snapshots of loved ones’ pains and triumphs, and generational memory produce a text so rich and vulnerable, the reader becomes more active witness than passive consumer.

Phi explains that he hopes his writing always serves at least two purposes: "First, as a reflection of people who don’t see stories about themselves in literature or in the mainstream. And [second],the other side of that is to open a window for people who don’t understand my experience.” What becomes clear is that these two aims underscore Thousand Star Hotel’s penultimate goal: to document Phi’s very specific experience as a working-class Vietnamese refugee raised in Phillips, Minneapolis for his daughter.

As a father, it isimportant for him to address the decades—generations—of silencing embedded in the way we are erased from the history and present of the U.S.:

This country doesn’t value Asian American studies at all. And that’s just a fact. You can look in textbooks and there will be no Asian American history. [My daughter] already has to struggle with that; she has no choice. She can either ignore it and assimilate or fight against it and learn about her own culture…And that’s part of why I wrote this book: I’m a Vietnamese person who didn’t learn shit about the Vietnam War in school. I learned from my parents—[learned] the trauma of it.

This trauma is central to Phi’s impetus for writing Thousand Star Hotel; when he and his then-partner, now co-parent, decided to have a child, they went to a clinic and filled out a survey intended to help the doctors identify possible risks. One of the questions was, “Have you or anyone in your family been traumatized by war?” Phi realized that his parent’s trauma, the foundation of his knowledge of Vietnameseness, of war, refugeeism, and difference, was a part of his lineage. Just as this was passed on to him as an infant during his family’s flight, so too would it be a part of his child’s life in Minnesota, where Asian American stories are still largely silenced.

To this end, Phi’s writing doesn’t just fill a gap, it is part of his daughter’s own history: “It’s a scary world; you could get shot, hit by lightning, killed in a car accident. So if something should happen to me, she’ll have her mother, of course, but in terms of my half of my daughter’s makeup—where is she going to [learn those stories]?”

This last question underscores the absolute imperativeness of Thousand Star Hotel. Much more than a set of poems, it is its own history: a chronicle of Phi's family, present, past and future. Spinning this history together from fragments of memory and reflection, the collection provides a critical thread in the fabric of Asian American literature, history, and activism—past and present.

Reflecting on the confluence of art, activism, and critique, Phi says that Thousand Star Hotel emerged in a moment where he began questioning the singularity of the truths we allow ourselves as creators and community members:

When I was younger, I really wanted to know what the right thing was—what’s the right thing to do, what’s the right stance to take, what’s the right position? And as I get older, I kind of embrace that multiple things are true at once, and often, those things are contradictory. There could be multiple truths that could be simultaneous. And that is not to say that we should be frightened into inaction. I think it’s actually the opposite; we should always be active and learning. I’m just not really sold on the idea of a single stance. I’m more motivated to understand what people do and why people do what they do.

This motivation has led Phi to include several poems about his loved ones’ experiences, pieces that force him to readdress his own approach to writing about pain, both his and others’:

I am trying to acknowledge how I’m complicit in the things that I criticize… I’m writing more towards things that I don’t understand, things that I don’t know. Things that are scary for me. And a lot of that, the really intimate stuff that I wrote about my family, is kind of in that direction. But it’s been hard to write—I want to do it artistically, I want to name my complicity in it, and I want to acknowledge the brutality of it.

This brings up difficult questions, however: “How do I do that without victimizing the people that I care about, that I write about in the poems?” Knowing the difference between his stories and those of his loved ones has allowed Phi to grapple with his personal responses to each:

I find that I have different defense mechanisms. [For example], the poem about my mom and how [some boys were yelling] slurs at her, “Go To Where the Love Is”: I remember the first draft of that was very aggressive because the defense mechanism was, “Okay, you’re reading this poem, fuck you,” you know, fuck whoever’s reading this poem, fuck me for writing it, fuck these little boys. That was my defense mechanism, to be angry and lash out. And I think that over a couple years of revisions and revisiting the poems, [that tone] didn’t feel right. I [ultimately] ended the poem with my mother’s kindness because it felt the most right, the most real. It felt the most appropriate, because it’s the most true. She’s gone through all of this shit, and for what she’s gone through, she’s a relatively kind person. So in a way, the entire book is a struggle about that: There are these difficult things and how do you write about them?

This act of parsing his own pain while working through his mother’s allowed Phi to consider how his early memories bleed into his role as a parent:

Things [end] up feeling very cyclical: things that I experience with [my daughter], I wonder if my parents experienced with me. Just the other night, for instance, she was asleep and outside the window of our apartment, there were a bunch of gunshots. Luckily, she didn’t wake up, but that was part of my childhood [too], and that’s just the neighborhood we live in... She is going to face discrimination based on her gender, or her race, or who she decides to love when she decides that.

This concern for his daughter’s understanding of the world coupled with an interrogation of her place in it as an Asian American, is a driving force in much of Phi’s writing. While Phi turned to a different parent–child relationship—his relationship with his father—as inspiration for A Different Pond, his soon to be published children’s book, his daughter was never far from his thoughts:

Something [my co-parent] and I decided on a long time ago, something that we still do, is that we read to our daughter every night. We either read to her or we read with her. As a parent, I’m very interested in what we read to our daughter. The [lack] of diversity in writers and characters is an issue, especially for an Asian American child in an urban neighborhood.

Encouraged by friends and family, Phi says he found his story in a poem: “I’ve been writing a poem a day for a while, and I wrote a poem about my father taking me fishing and thought maybe this could be a book. I met with a children’s book writer, and he said that’s a great theme for a book because there are a lot of father–son books about fishing, but they’re recreational, father bonding books; they’re not about race and class and war.”

Several children’s book authors agreed, sitting down with him to think through the story: “It’s almost like writing in a form—it’s like learning how to write a sonnet or a sestina; there’re certain rules and techniques that you use, and I didn’t know any of them, so [the authors] gave me tips.” Several members of the children’s book community encouraged this book particularly because poets are “used to the idea of form—of brevity and succinctness”; it is often easier for them to transition from one type of writing into the other.

While Phi developed new tools and received a great deal of community support, the manuscript did not yet have a home. During that period, Phi reviewed one of his daughter’s favorite books at the time, Here I Am (Capstone) written by Patti Kim and illustrated by Sonia Sánchez, on his organization’s website. By chance, the publisher saw his review, reached out, and eventually, made Capstone A Different Pond’s home. Then came the question of who would illustrate it. Capstone invited Phi’s input for an illustrator, and both agreed that Thi Bui, who recently released her own family’s story, The Best We Could Do (Abrams) as an illustrated memoir, was a fantastic fit. For him, it was also another lesson in form:

What’s really different about working on a children’s book with an illustrator is that those of us as writers are used to doing all of the heavy lifting by ourselves. We have to describe everything. And what was pretty amazing and also kind of world-shifting working with an illustrator was, “I don’t have to say that—she can illustrate it!” I can’t explain how mind-blowing that is. And it’s very powerful collaborating with someone.

Like much of Phi’s poetry, this book is simultaneous, multiple, about class and race and family, thick with love and loud in its subtleties, themselves a significant piece of the collaborative work of author and illustrator:

Thi’s artwork speaks for itself; she just did a phenomenal job. And even though our experiences as Vietnamese refugees are very different, there were just some things that didn’t need a whole lot of explaining. [For example], she would say, “I need an idea for something [to put] in the background here: What do you remember about your childhood?” And I would say, “nước mắm in a mayonnaise jar,” [and] she knew what that meant immediately. There were several things of that nature that were just super easy. And that’s just on the superficial level; on the larger level, she completely understands the melancholy and the struggle of being a refugee, and that comes across I think in ways that are very subtle.

As Phi explained, while on the surface A Different Pond presents as a simple parent-child narrative, it is, at heart, a refugee tale. In the case of both books, “The [Vietnam] war haunts my family, and it haunts my story…it was important [to me] to let the war be something that definitely affected my life, but I think in ways that [because I was 3 months old] are not as clear as things that I remember.” In this way, a father–son story about waking before dawn to fish for dinner is also a story about class, about personal and cultural touchstones in forced diaspora, and the small moments of familiarity, care, and practice that make family what it is.

Phi closed our conversation, saying: “I am very proud of the book. I hope it’s useful for kids and families, and I’m glad to be attached to something that Thi is involved in.”

As readers with two excellent books to look forward to, we should be glad as well.

“I used to fish by a pond like this

one when I was a boy in Vietnam,”

Dad says, biting into his sandwich…

Dad tells me about the

war, but only sometimes.

—Bao Phi, A Different Pond