Author Interview With Christine Hyung-Oak Lee

Interviewed by Alexander Chee

Author photo by Kristyn Stroble

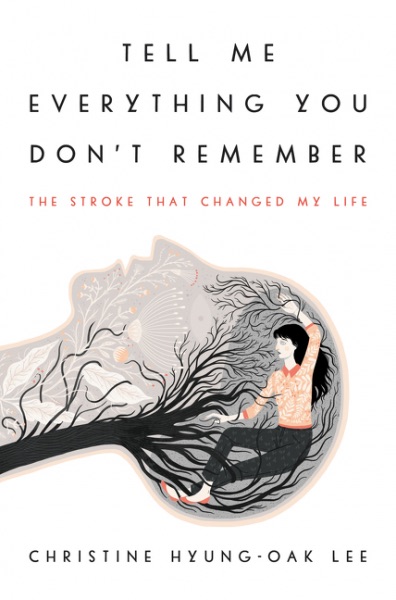

Cover design by Sara Wood;

Illustration by Lisa Perrin

I first met Christine Lee when she emailed me in October of 2008 to ask if I would agree to an interview with the journal Kartika Review—this journal. She also came out to me—I already knew her. She had a blog identity, and had been a regular reader and commenter on Koreanish, my blog at the time. She eventually revealed two blogs—one about cooking, the other, about recovering from a stroke she had at age 33, an unusual but not unheard of condition for someone that young that left her living quite literally in the present and struggling to reconstruct her thought processes and her life.

It was a commonplace of the Internet at the time, a little before Facebook and Google’s Real Name controversies, that we had these digital identities. But I think of her as being a writer who built herself in secret this way, before eventually emerging into the light. And what a light it was.

Two years ago, an essay she published at BuzzFeed about her stroke went viral, and in the aftermath she found herself courted by agents and publishers. On the strength of the interest, and the manuscript, she sold her debut memoir, Tell Me Everything You Don’t Remember, and her debut novel, also, in a rare two-book deal. She became an overnight success who had been working for many years—a classic of a kind. The memoir has since been published—she has debuted to much acclaim—and what struck me about the book itself was the crystalline quality in the writing, a subtle lyricism almost at odds with her in-person persona except that both are the real Christine.

The Christine I know is a mix of out-spoken and self-effacing, funny, even a little slapstick, with a penchant for bawdy jokes in person. That is who she is with her friends. The Christine Lee who goes out to the public is terrifically organized, still funny, but a listener, who can think on her feet and make you feel entirely heard before she herself delivers some of her hard-earned wisdom in response to your questions. You have probably been to one of her AWP panels—she has a knack for organizing them. She bears something of a resemblance to Margaret Cho also, and has regularly been asked if she is her, even mistaken for her, and she takes it in stride—and has even brought it up with Margaret Cho.

I don’t really know who she was before the stroke, except from what I can intuit from her memoir. But the friend I know is literally a self-made woman, someone who brought herself back from the edge of nothingness, a process that, in a sense, made her who she is now. And that person is formidable, kind, and so incredibly talented.

We conducted this interview by email in June of 2017.

Kartika Review: You won an unusual opportunity, afforded to few writers—maybe not even any writer I’ve known—to have a house acquire your debuts both in fiction and nonfiction. Is there even the slightest connection between the books, besides you?

Christine Hyung-Oak Lee: Thank you, Alex. I’m humbled by these outcomes. Part of me wants to call it luck, but I know I’ve been writing hard for a decade. When editors and agents reached out to me, I remember several asking me, “Where have you been?”

I’ve been in my pajamas, writing my novel, I told them. In this way, publishing cannot happen without writing. Writing is not publishing.

I’ve thought quite a lot about the connection between my two books. They seem very disparate from a distance, but they both revolve around the theme of monsters, ones that suddenly arise in life and disrupt normalcy. There is the stroke, which reared its head from seemingly out of nowhere. And there is the golem, which my characters create to help them in their mission.

Also, there is this: I was writing my novel when I had the stroke that left me with a fifteen minute short term memory. I couldn’t, as a result, write fiction. And it was my top goal to be able to write fiction again—so in essence, the novel is part two of my life story. It is the living sequel to my memoir.

KR: What was it like going viral? We spoke a little about it at the time, but any reflections at a distance?

CHL: It was discombobulating—friends and friends of friends started posting links to the essay on Facebook and Twitter. My inbox began to fill up with emails from readers. At first, I was confused—what was attracting all this attention? And then I realized—the essay itself is attracting attention. I’d been writing in the dark and in relative anonymity for so long that to have a light cast upon me and my writing felt strange. But at the same time, nothing changed—I was still a single mom, still working, still navigating my friendships, and still figuring out how to make ends meet. My role as mother, my friendships, and the reality of my day to day life kept me grounded. Thank goodness. There’s nothing like a toddler’s tantrum to make you realize you’re not anything special; you’re still trying to raise another human being and cleaning up vomit.

KR: Had you always written both fiction and nonfiction leading up to this?

CHL: Aside from my blog, I had not written much nonfiction. I was solely a fiction writer. I didn’t take a single nonfiction workshop in my MFA or at any summer workshop offered me, and I now regret not having done so.

I shied away from writing nonfiction for various reasons—some of which had to do with my idea of privacy. But it was Chris Abani who told me, when I once protested sharing a personal anecdote in workshop, “Then why do you write?”

Indeed. Why do I write, if I can’t share what’s happened in my life? In hindsight, it was he who emboldened me to explore the world of personal essays.

KR: That’s a fascinating insight from Chris. We know about the memoir—what can you tell us about the novel?

CHL: My novel is about two Korean immigrants in 1972 New York City—they’re in America to find a long lost relative. In the course of their journey, Yong and a man nicknamed the Frog build a golem out of North Korean soil that they have brought with them to aid in their search. It is a cross-cultural retelling of a Jewish tale.

KR: It seems corny to say I can’t wait to read it—but I can’t wait to read it. It’s often remarked on that Koreans are the “new Jews,” but some are actually Jews, as your experience shows. What has it meant to you to write about both your Jewish faith and being Korean, imaginatively? And can you say what you are learning in the process?

CHL: Drawing from my Jewish background feels natural, even though it may surprise others to learn I’m Jewish at all. Culture has so many intersections and I know I’m at an unusual one, being Korean and American and Jewish, as well as a single mother and stroke survivor and daughter of immigrants and Californian and New Yorker. But it’s the mission of every writer to bring out their unique perspective of the world—and writing from my sparsely populated intersection makes me feel more seen.

There is a huge responsibility in carrying on adopted cultures. I am not a born Jew and I realize that I am writing from the outside. But I hope that my experience as a person of color and woman and minority has taught me to respect narratives outside of the ones I’ve inherited.

The Golem of Seoul, my novel, has waited for me to mature, and it has taught me many lessons. My novel and I have a symbiotic relationship; I breathe life into the characters and plot, but at a certain point, I must listen to them and to their world and heed their desires. Every time I get stuck while writing the novel, it’s because I’m being a tyrant and telling them what to do without considering their needs.

I started writing The Golem of Seoul when I was thirty-one years old, more than ten years ago; I’d not had a stroke and not had a daughter and I’d not lost my marriage. Yet. This novel has seen me through those challenges, and it has benefited from my growth.

KR: It sounds as if, in a sense, it is maybe a Golem for you also.

CHL: Yes absolutely, my novel is a golem. And it too, has brought me to life.

KR: How do you feel being a part of an Asian American literary community has helped you as a writer along the way?

CHL: The Asian American literary community is my home. I minored in Asian American Studies as an undergrad, and I remember how I suddenly felt at home those last two years in college. It was then that I also began reading Asian American literature in earnest—I remember reading Chang-rae Lee’s Native Speaker when it first came out, and then going to his reading at Cody’s Books and dreaming of that life—and then pursuing him for an interview when I was editor at Kartika Review and experiencing my own career development around relationships with such writers, from reader to acquaintance to somewhat-cohort. He was, alongside Maxine Hong Kingston, a pioneer for me. And whether he knows it or not, he built a ladder behind him for people like me.

On a craft level, our audiences must be very specific—the reader should feel like she is eavesdropping in on a conversation. To that end, I don’t translate Korean words in my writing, because I am writing to my base, to the community from which I come, the people who understand, in hopes that someone might want to eavesdrop and learn.

And on a support level, no one has been more supportive of me and my work more than the Asian American literary community. I recognize that. Asian American readers “get me” more than anyone else. Thank goodness.

KR: You were a blogger a long time before this—was that at all helpful when it came time to publish a book? This is what publishers imagine.

CHL: Blogging helped me find my writing voice. And it has always been a space for me to do some “low stakes” writing, where I’m putting out my thoughts without pressure. It is a haven.

So when I get stuck, I try to capture that feeling. And of course, since I blogged throughout my stroke and recovery, it was immeasurably helpful as a resource while writing my stroke memoir, Tell Me Everything You Don’t Remember. The biggest deficit from my stroke revolved around short term memory problems, so present me is very thankful to past me for having been so diligent and determined about documentation.

KR: That’s interesting to me, as that is exactly the sort of creative protection Elena Ferrante sought in her pen name… What have you learned about social media and writing this far in?

CHL: Social media has evolved. I was on the net when there were 500 women on the web in the early 1990s. It was a small town then, and now it feels huge. I’ve made so many friends via social media. I’m thankful for that. It makes sense as a writer that I’d form bonds more easily through written words than in spontaneous physical interaction.

But these days, it’s a large city. I am at a crossroads; do I broadcast, or do I continue to operate with the intention of being more intimate? So far, I’ve chosen the more intimate path, if for the reason that I don’t know how to be a public person. And I’m not sure I want to be.

KR: Would you return to blogging privately then?

CHL: I would. And I probably will. For now, I’m scribbling in my Moleskine journal—doodles to ideas to thoughts to the beginnings of essays to collaborative work with my daughter, who will begin with a scribble which I then complete. I wish people still read blogs. Do they read blogs? I still do.

KR: What was the biggest lesson of your nonfiction debut, the one nothing had prepared you for?

CHL: I looked for love and acceptance when my book came out; all my wounds opened in anticipation of redemption. But your inner life does not change when you publish a book, and I’d forgotten the lessons I’d learned about perfect readers.

Writers have “perfect readers”—the readers who understand exactly what you’ve written, but these are always few. In this way, the MFA workshop is great training ground for book reviews and public reception of one’s work—you learn that not everyone, which includes very intelligent people, will love your work. This includes racism, and the fact that readers aren’t prepared for memoirs by people of color, which are relatively rare in the publishing landscape.

I was prepared to do the work of publicity, but unprepared for the emotional challenges of putting a book out in the world. It’s a thrilling experience. But it’s also a bruising one. I’m indebted to friends who kept me on message, who kept me fed, who kept me comforted. My community, most of which are Asian American writers and readers, is my home.

As an aside, but of importance: I learned a lot about doing live interviews. Make sure doors are locked, and everyone in your house knows to keep quiet during live interviews. Two out of my three live interviews were interrupted by either my crying preschooler looking for me or a partner who strummed his electric guitar in another part of the house.

KR: And as you prepare for your novel, what will you do the same, and what will you do differently?

CHL: I will inevitably send The Golem of Seoul out into the world with the same hope I had for Tell Me Everything You Don’t Remember—whether or not this is wise, I don’t know. But I know I won’t help doing so, even though I will likely protect my heart a little more than I did with my memoir. While I didn’t do a book tour for my memoir, I may do so for my novel. I have been told that every book release feels different from the others, so I suspect that the experience will not be the same, regardless of what I do or do not do!