Author Interview With Jiwon Choi

Interviewed by Stephen Hong Sohn and Paul lai

Author photo by Matthew Beckerman

Cover design by Marie Carter

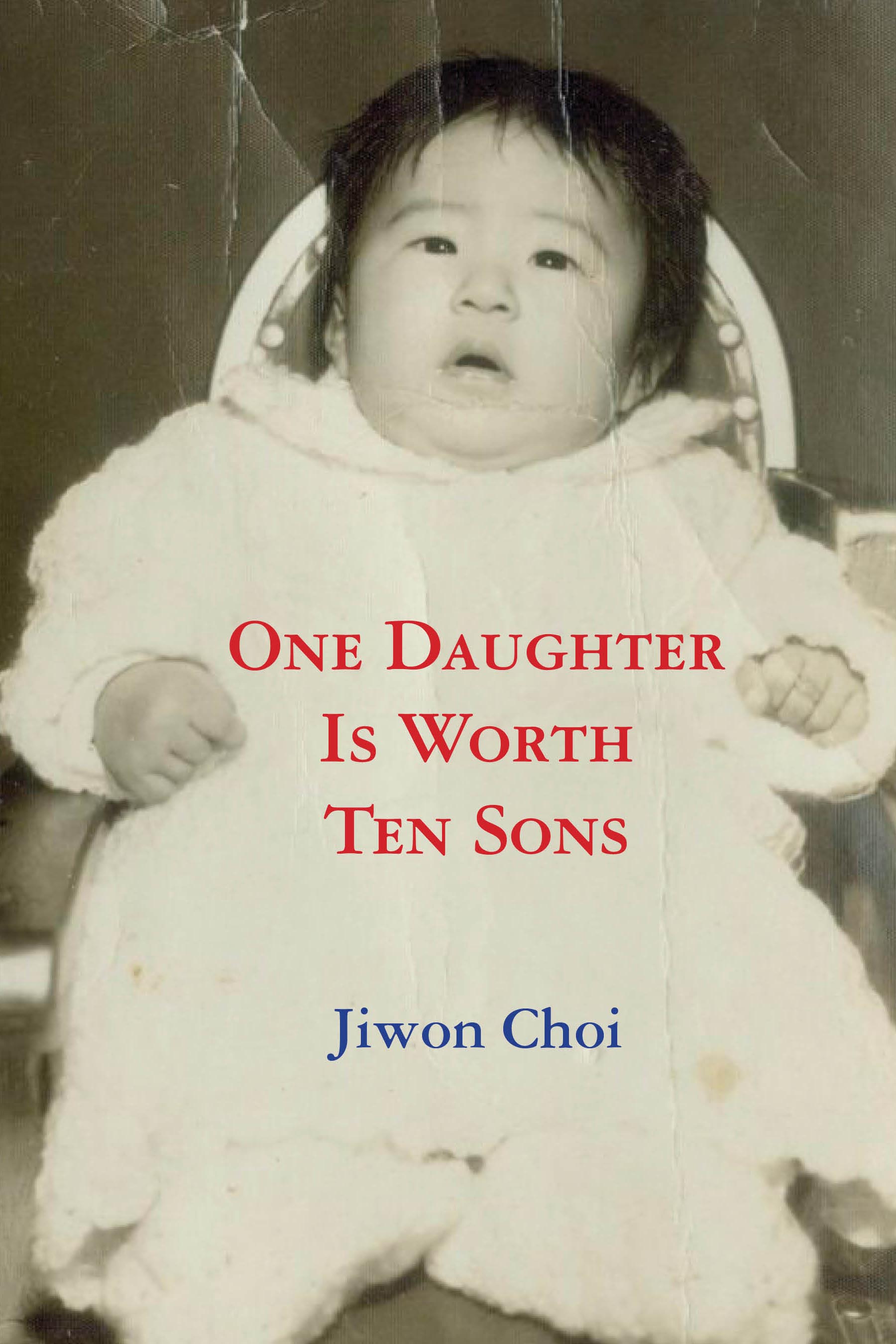

Jiwon Choi's debut poetry collection, One Daughter Is Worth Ten Sons (Hanging Loose Press, 2017), is an expansive world of words—careening from Korean proverbs to Greek mythology, Cinderella to Erik Estrada, Biblical stories to Jane Austen. The poems also range in scale from observations of a personal nature to world historical commentary. These poems are thought-provoking, dense in allusions and startling imagery (“then I spy the half-eaten / pastrami on rye / gutted and strewn”) that transform ordinary objects into philosophical ones. We are lucky to hear from Choi in the following interview.

Kartika Review: What’s the importance of interlingual poetics/use in your work (why use Korean characters in some areas and not others)?

Jiwon Choi: The Korean characters were strictly for the proverbs so that’s why they appear. Though I suppose you could have the proverb solely in English, I find it aesthetically appealing and powerful to see the Korean characters alongside the English.

KR: The title obviously evokes problematic patriarchal paradigms of many East Asian cultures, particular Korean ones as well, so perhaps you could further explore how your work finds inspiration in upending this paradigm?

JC: This paradigm has been in place for a lot longer than I’ve been alive or writing poetry, and I acknowledge how these patriarchal norms have become woven into the social fabric of our lives to the point where we don’t always take notice. I don’t necessarily write to upend these patriarchal norms, as much as I write to find my way out of darkness. And by “darkness” I mean the particular hardships and challenges that are unique to each of us based on our life stories and situations.

I grew up in New York City where Confucianism isn’t up in my grill like it might be in Shenzen or Seoul. NYC–– an urban mecca populated by the world’s diaspora where you need to get along with everyone and your dark-ages thinking about women and their “place” in society might not go over so well.

Who stands to gain from keeping this gender status quo anyway––the government, corporations, males in general? Not women, right? Ultimately, I think that the force and will of our modern times and its people (that’s us!) will be what knocks down antiquated notions of gender and hierarchical roles a peg or two.

KR: How do you situate yourself in terms of a poetic genealogy and your poetic forebears (you do make references to a number of different poets such as Ko Un/Anne Sexton, for instance)?

JC: Certainly, I feel the impact of my poetic forebears. I take inspiration and insight from poets who work to bring light into the dark. I look upon Philip Levine as my poetry father, a poet who worked to give voice to the voiceless and highlight the lives of working America. Though Levine never met me, he wrote for me, paying homage to my life and plight as a working stiff and an outsider. I look to the work of Yusef Komunyakaa to provide added value to my ongoing poetic expression. And when I come across works by Korean poets, well and little known, I find that they fill in the gaps on my sense of Korean-ness. Years back, I found a collection of translated poems by kisaeng poets from the 16th and 17th centuries, and it revealed to me another layer of the Korean experience through the eyes of courtesans who straddled the line between being valued for their artistic “skills” and Confucian restrictions.

I understand the reality of writing (art in general): Someone was there before me, and one of my tasks is to figure out how to create a space for myself, a way to make my voice distinctive. Not to reinvent the wheel, but to make the wheel turn in the direction of my choosing.

KR: Your poems often find a delicate and elegant balance between the personal and the political, the contemporary and the historical; given the many scales and contexts that you're working with, what was the process of organizing this collection and making it function with a structural conceit in mind?

JC: Forming the spine for this manuscript took some doing. I had pages of poems in various stages of edits, and I looked at these loose sheets as a shapeless mass––ugh! Some of the poems were from years ago while others were recent. Could they come together? Luckily, I write at a snail’s pace, so the structure of this collection appeared to me in the form of my personal history. Does that sound self-indulgent? Sure, but you can’t forget that an aspect of art is to research oneself in order to become better able to understand one’s art and its cultural contribution to the world. Basically what became clear was that I was putting together an homage to my father who’d passed in 2006. And that is not to say that all the poems in this book are about my father, just that I was (and will remain) affected by his death––insomuch that I cannot come to an emotional resolution. I acknowledge that, as a living person, coming to an understanding about death and dying is extremely difficult because I’ve nothing to compare it to.

KR: I absolutely adored “Back to 1951” (the nature of trauma as it manifests across generations) and noted the especially strong lyrics throughout that link father to daughter. Can you remark further upon this as a mode by which the collection finds some general coherence?

JC: Coherence? I’m not sure I’ve fully arrived at coherence, but working to make connections in my work is essential. Weaving images, experiences, and emotions into a relatable tale is the way I want to reach people at their core––the way I was touched by the words and ideas of the writers I love and trust.

KR: The question I love to lob at poets: Why poetry? What is it about this form is the right vehicle for you?

JC: Poetry is in everything. Everything is in poetry. Our humanity is rooted in poetry because poems are the stories of our lives. I write poetry because I am made up of these stories and I want to share them so we can all get out of the darkness together. I think that the elements that make up poetry is the common thread that runs through so many art forms––painting, music, sculpture, dance, etc. Poetry is the eternal dialogue taking place between your brain and your heart.

Ask me why did I choose poetry? I’m not sure I had a choice.

KR: Your collection includes a number of poems in a series titled “Koreans in Proverbs” in which you spin out intriguing, poetic considerations of Korean-language proverbs. Proverbs are an interesting linguistic form, often culturally-specific and characterized by morals or statements that reveal specific worldviews. How did you come up with the idea for these poems?

JC: I went to live in Seoul back in 2002 to see my parents who’d moved back in 1997. My father had had enough of the U.S. I planned on staying for a year, but stayed for three. In that time, I met Koreans who appeared to embody some of these very proverbs-to-poems in my book. As I grew up relegated to the Korean diaspora, I had to get my information about Koreans through literary and cultural modes/outlets. So I see these proverbs as a gold mine of specific cultural notes on a group of people who manage to be both kindred and distant to me.

I learned some things about being Korean and American while living in Korea––straddling two cultures and worldviews can make you a little crazy and not necessarily smarter––heightened perception can make your life harder because ignorance is bliss. Ultimately you grow a tough outer layer and do not shy away from situations that make you uncomfortable.

KR: I noticed references to some American popular cultural phenomena scattered throughout your poems, particularly repeated, sometimes oblique, references to The Wizard of Oz. How do you decide to pull in these references in particular poems?

JC: How lucky we are to live in America. Despite the ugly stains of slavery, the still-alive plantation system, native genocide, and the prison industrial complex, we live in a country that has gotten many things right––freedom of speech being on the top of the list. References to life growing up during the seventies, eighties, and nineties offer up a glimpse into my life and my point of view. These cultural references are communal experiences––a creative commons to be shared and used. They can offer a platform for what Adrienne Rich envisioned as a “common language.”

And I will remind us that these popular cultural references (like the theme of displacement in The Wizard of Oz) were not created in a vacuum—they were borne out of our psyche and a part of our life force. They embody us, and we embody them. In the end, what strikes me as true and honest is what finds its way into my work.

KR: Switching gears to your writing process... Could you tell us a bit about how you write your poems usually (when, where, etc.)?

JC: This first collection took me about five years to complete. Maybe it’s just numbers, but five years feels like a long time. I wrote this book in fits and starts due to work and family struggles—taking care of my mom and aunt who both have dementia. I found myself writing in bars and coffee shops—definitely on the F train—around town to get my edits in and wrap up by deadline. I have gone on writing retreats and attended workshops to get the best out of my writing, but at this point in my life, I feel the best when I’m in a quiet place where I can hear my thoughts––early mornings in my apartment, on our small deck, or a bench in Prospect Park.

I also find myself eavesdropping on people to hear their cadences and learn how people talk when they think no one can hear them. This is all a part of the research you’re tasked to do when you’re writing poetry just as much as you would a novel or another literary piece. And if you’re writing about your own experiences, then what better research subject than yourself. Know thyself.

KR: Some of your poems are very rooted in New York City geography, and your author bio notes that you are located in Brooklyn. In general, what do you think of where you live, and how much do you find the city to inform your poetry?

JC: I grew up in upper Manhattan before moving to Brooklyn, so I am an urban baby to the core. I grew up with a movie theater down the block, the Olympia Theatre now long gone, where my parents took me to see Taxi Driver when I was seven. My neighborhood proper was listed in the NYPD’s top ten most violent neighborhoods—you know it was the classic drive-by routine back then in the seventies and eighties. I used to think those gun pops were just firecrackers. But I also had Riverside Park where we sled down hills on garbage can lids on snowy days, picnicked on bologna sandwiches in the summer, running wild all over her playgrounds. My NYC state of mind informs how and what I write in an indirect and nuanced way––Cortes riding the R train, bittersweet memories of my high school love on Rockaway Beach, or cabbies in Williamsburg––representing an urban mosaic that is equal parts ghetto, fairy tale, and Anne of Green Gables nostalgia.

KR: What inspires you to write?

JC: I am compelled to write so I can make sense of my childhood––a source of both my angst and power. I also want to create work that connects to people, work that offers enlightenment—a way out of the darkness.

KR: What are you reading these days?

JC: I am a smorgasbord type of reader. I surround myself with a buffet of books and then read at my leisure. I recently finished Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me, which was both devastating and edifying.

I am rereading William Julius Wilson’s The Declining Significance of Race as a complement to Ta-Nehisi Coates’s heartbreaking book. I have also started Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run.

I read poetry. I tend to go back to my touchstone poets for sustenance: to name a few there are Philip Levine, Louise Bogan, Charles Simic, and Lois-Ann Yamanaka who offer reassurance and grit. Yusef Komunyakaa offers enlightenment. And when I do veer off my well-trodden path, I try out new voices: Ann Carson or Terrence Hayes. But I will admit I am provincial when it comes to my poetry reading habits: Unlike Red Riding Hood I’m good at staying on my path in the woods.

And, of course, I read my cookbooks: Sundays at Moosewood Restaurant, Mad Hungry, Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone, A Korean Mother’s Cooking Notes, The Silver Spoon, and Dori Sanders’ Country Cooking for dinner ideas and good examples of organized writing.

KR: Finally, do you have any advice for poets seeking an audience and publication?

JC: I think it’s a good idea to be in touch with yourself about why you’re writing poetry. Know your motivations and be honest about why you’re sharing and exposing yourself and your work to others. Be aware that critique and criticism of your work might not always be positive or pleasant.

I say that on the heels of having recently been invited by a librarian to talk with some high school seniors about my work as a part of their guest writers program. These high schoolers and their questions about my poetry were no joke––they asked me about my motivations, about my process of writing, why poetry? And some of them might even have been a bit skeptical about its place in their modern times, and I can’t begrudge them their feelings. But what they got is that writing can be a way out of the dark and that they can be a part of that journey.

I am grateful for this experience because I really got to hear myself talk about my work and understand that whatever I said to them had to be 100% because they deserved it and because they could sniff out any lie or subterfuge.