Author Interview With Vanessa Hua

Interviewed by Paul Lai

Author photo by Marc Puich

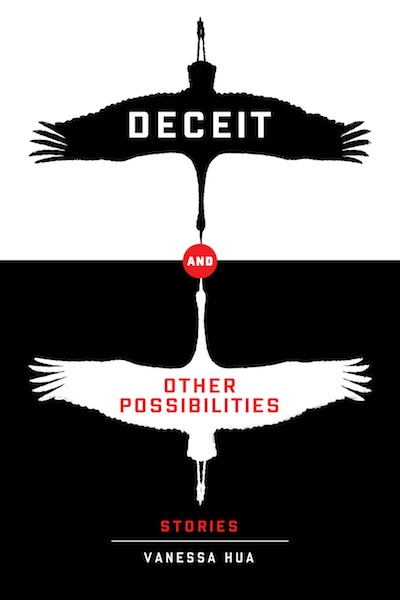

Cover design by Josh Korwin

Vanessa Hua's debut collection of short stories, Deceit and Other Possibilities (Willow Publishing, 2016), spans a cast of characters, continents, and oceans—all connected somehow through contemporary West Coast communities. The characters are flawed, complicated humans who struggle to present themselves as good people—both to themselves and to others. Their deceit is both frustrating and intriguing, often serving as the engine for the plots that lead to messy situations. Yet, Hua's authorial eye offers up these characters in an empathetic light—as people to be seen and heard, even if their actions are not always to be lauded.

Hua also turns her discerning eye to characters from different ethnic backgrounds, immigrant histories, and socioeconomic backgrounds. As a whole, the stories thus offer a wide-ranging look at people whose lives overlap in California, even if they are unaware of each other. Subtle details and some characters reoccur across stories to create an even greater sense of interconnection.

Hua is an award-winning journalist who has written extensively for national publications, and her keen eye for both the personal experiences of individuals and the macro forces that have pushed and pulled people across lands and nations is evident in both her journalism and creative fiction. She is working on two novels for Ballantine, A River of Stars (Spring 2018) and The Sea Palaces. We're excited to interview the author in this issue.

Kartika Review: One of the things I love the most about Deceit and Other Possibilities is the setting of the stories in California and their trans-Pacific connections around the turn of the 21st century. This is the world I grew up in, so I felt a deep sense of familiarity as I followed the characters. How do you go about providing the setting and context for your stories, and how do they unfold in relation to how you depict the characters and the plotting of stories as you are writing?

Vanessa Hua: Well, we did figure out that we came from the same hometown in the Bay Area! I’m glad to hear that the settings felt familiar and true. Immigrants and the children of immigrants are everywhere, cities and suburbs, and that’s reflected in my stories. Setting is essential to developing my characters; that is to say, what they see, taste, touch, smell, and hear, and how they sense the world reflects who they are and their state of mind. Their communities—social, economic, ethnic, geographical—determine how they can navigate the world. It’s been said that character is fate. So too setting.

KR: As I read your story collection, I was intrigued by how many of the stories seemed to be set in a contemporary moment but also nevertheless seemed to refuse being pinpointed in a particular year or even decade. Especially since your second forthcoming novel is a historical one, set during the Cultural Revolution in China, I'm curious how you think about time in your writing. How do you decide when to set a story, and how do you indicate the time of the story (or not)?

VH: I put together my collection over a decade, and as I wrote each story, it reflected the present moment (aside from those such as “For What They Shared” in which I wanted to reflect a particular time in immigration policy). I hesitate to overuse songs and name brands to signify character or an era; so often, it can quickly get outdated or the reader may puzzle over or miss the importance of a detail altogether. I’ve talked to students about whether they’ve heard of Saturn cars or Clearly Canadian sodas (from my youth). No, they said. So too their references to Grey Goose vodka will turn fleeting someday.

With “Loaves and Fishes,” I worried that backseat video panels were starting to disappear from airplanes (it’s a plot point) but then realized, with relief, that they will likely remain on international long-haul flights. I’m not going to pretend that cell phones don’t exist, as much as such technologies now stymie authors who don’t want their characters to have all of human knowledge at their fingertips! My stories are meant to be in the near-past or near-future—the concerns of my characters are contemporary but also timeless.

As for my novel set during the Cultural Revolution, I will reference specific, documented moments from that period—but as a writer, I’m most interested in the gaps in history, those characters missing from the official record and their dreams and their fears.

KR: The characters in your story are primarily Asian American but from different ethnic backgrounds and immigrant generations. In other interviews, you've discussed talking to friends and others who come from these other backgrounds as a way of understanding your characters' perspectives, drawing on your journalistic experience in interviewing people to tell their stories. I'm curious what your thoughts are on the responsibilities of writers, editors, publishers, and readers when creating or encountering characters from different backgrounds. I've been following conversations in the children's literature world, like We Need Diverse Books and #OwnVoices, that advocate for increased publication of and attention to authors of color and indigenous authors as well as a strong privileging of books with characters that align with their authors' racial backgrounds. How do we write and read characters of color responsibly?

VH: As a journalist, I’ve long had the opportunity and privilege to interview people from many different backgrounds. I try to get out of the way as much as possible as they tell their stories. People of color—because of the lack of representation, and because of pervasive, pernicious stereotypes—are so often denied their humanity and denied their stories. Whether in fiction or nonfiction, I begin from a place of humbleness, not arrogance. I want to understand their circumstances and their motivations, in my attempts to write responsibly. Even when someone shares my background—American-born Chinese, suburban-bred—I can’t make assumptions. Consider how people can be different within a family, or even within themselves over the course of a year.

I support the #OwnVoices movement and am eager to read authors whose works are new to me. And yet, I also understand that these stories reflect one author’s perspective and not an entire community. We are not a monolith. We are multitudes.

KR: Relatedly, I like comments you've made in other interviews about the need for readers to remember not to read characters of color as standing in for everyone of their racial backgrounds or even as metaphors for their communities. Beyond the individual act of reading, what are some things that we can do to foster this understanding?

VH: Reading is vital to fostering empathy and expanding your worldview to include different perspectives. And yet, it’s not enough. I was just reading a study that found out among white Americans, their network of close friends and family is 91 percent white! Blacks, Asians, Latinos, and mixed race each clock in at around 1 percent in the social networks of whites (the rest is “other” or “don’t know/refused.”) Three-quarters of Americans don’t discuss important matters with any minorities. We need put ourselves out there, to meet and interact and work together and share a meal or take part in a protest with people outside our bubbles.

KR: You've talked about the differences and similarities between journalism and fiction for your writing. I like the idea of giving voice to people who do not often make it into the public record as something you see in both kinds of writing. And I like the idea of fiction as a way of going beyond reporting on people's stories—to imagine their interiority and the more subjective aspects of their experiences. How do you understand the different audiences for journalism versus fiction? Does your anticipated reader shape how you present people and ideas differently?

VH: In fiction, I get to make things up! I get to sink into a character’s interiority in the space that a short story or novel allows. With journalism, not only does the audience expect to read something that “really happened” but also expects a certain form. Not that there’s a formula, but I’m presenting sources and making arguments within a certain length (say, 800 words for a column or 2000 words for a feature.)

KR: In other interviews, you've encouraged aspiring writers to join literary communities in addition to reading widely and writing regularly. What have you found to be most helpful in the different types of literary communities that you've engaged (MFA program, residencies, conferences, reading series, critique groups, etc.)?

VH: They’re interconnected. I have a critique group that’s been together since 2004, and one of the members runs a reading series where I’ve read and to whom I’ve referred friends I met at writing conferences. Friends I met at residencies and writing conferences showed up to my events. I attended AWP for the first time this year and reunited with friends from my MFA program. In and across these circles, I try to connect people. I also share opportunities (one friend landed a residency and was longlisted for an award, another friend got a teaching job and won a book contest after I encouraged them to apply). So much of writing is solitary and difficult, it’s important to help each other out—people in turn will help and support you. It’s not quid pro quo; it’s friendship.

KR: Your debut collection was the winner of the Willow Books Literature Award, and you've mentioned that short story collections can be tricky to publish outside of competitions run by smaller presses. How did you learn about what kinds of books are publishable? What advice do you have for writers on learning the ins and outs of publishing different types of stories and books?

VH: When you’re writing, you have to put publishing out of your mind, impossible as it may seem. You can’t predict the tastes of editors, their moods or whatever else is going on in their life if and when they reject your work. Send it somewhere else and keep writing and revising. That said, if the journal publishes experimental work and yours is traditional in form, if the agent only represents thrillers and you have a quiet literary novel, you probably shouldn’t submit there—take the time to understand what might be a good fit for your work. After that due diligence, if you are still hesitating, remember: your chances may be slim, but if you don’t apply, you’ll have none at all. Get used to rejection, though. It’s constant in a writer’s life because what is publishable remains eternally subjective. What matters most is whether you can live with what you wrote. You’re the one who is going to be spending months and years on it, away from your family and friends, sunshine and fresh air.

KR: Congratulations on your book contract for two forthcoming novels! How are you approaching the task of writing these two novels? Has anything changed from your approach to writing short stories?

VH: Thank you! With novels, it’s a marathon—though I hesitate to say that short stories are a sprint. But like a poem, a short story is more tightly focused on a moment. A novel is much more expansive, following the arc of a character’s journey, whether that’s over the span of months, years or a day. I must admit, both novels started as short stories, which made it less daunting than saying, “Today I’m going to sit down and start a 300-page project.” Slowly, steadily keep writing until you finish you draft, and do what you can to keep all parts of the project in your head; in a long project, different parts can get amnesia from each other. I use a pdf-to-voice program so I can listen to my draft while commuting and going for a run.

KR: Do you have any authors you're eagerly awaiting new work from?

VH: So many! I’m very much looking forward to R.O. Kwon’s Heroics, Kirstin Chen’s Bury What We Cannot Take, Ingrid Rojas Contreras’s The Fruit of the Drunken Tree, Kaitlin Solimine’s Empire of Glass, Julie Lythcott-Haims’s Real American, Adam Pelavin’s Existence Proof, Lee Kravetz’s Strange Contagion, and Laurie Ann Doyle’s World Gone Missing.

KR: Any last words?

VH: Thank you for reviving Kartika, taking the time to ask such thoughtful questions, and fostering literary community, as always.