Author Interview With Stephanie Han

Interviewed by Tamiko Nimura

Author photo by Kalei Han Simms

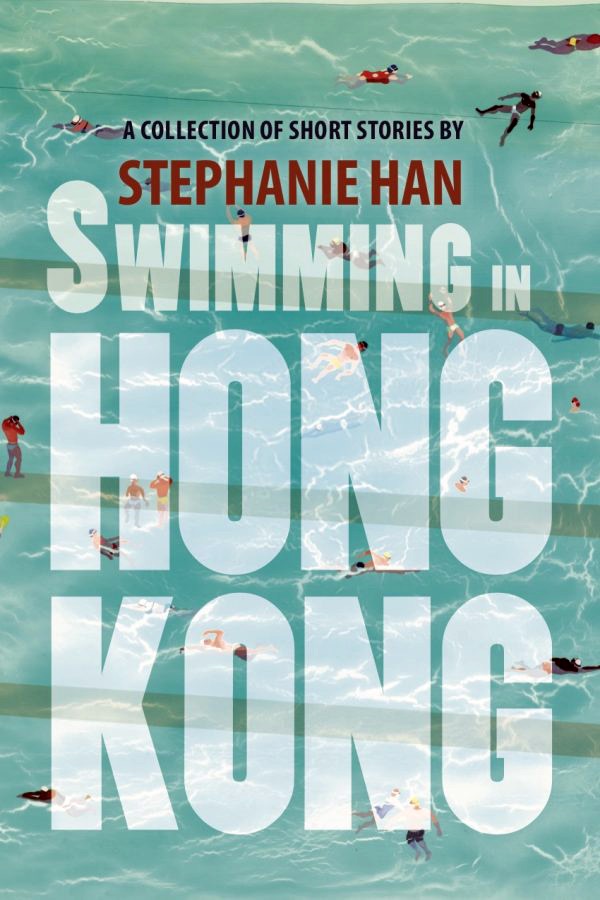

Cover design by Clarinda Simpson;

Art by Fan Yang-Tsung

Places brought me into conversation with Stephanie Han, although we have never met in person. I live in Washington State, home of the publisher for her debut short story collection, Swimming in Hong Kong (Willow Springs Books, 2017). A mutual friend introduced us, and we discovered that we have both been scholars of Asian American literature, PhDs, writers, teachers—all with ties, however loose, to Washington. Han is an award-winning writer who’s received recognition from the Paterson Prize (winner), the AWP Grace Paley Prize for Short Fiction (finalist), and the Spokane Prize (finalist). She divides her time between Hawai’i and Hong Kong. She received the first PhD in English literature from the City University of Hong Kong.

Place, and its implications for identity, is a core theme of Swimming in Hong Kong, a collection which won the Paterson Fiction Prize in 2017. It’s a collection that moves deftly between a variety of narrators—from English language teacher to Korean American adolescent, from trophy wife to older working-class Hong Kong man, and much more. Despite these differences, Han’s command of these multiple voices is surefooted and confident. Her characters embody the predicament of short story protagonists: they are all at someplace, sometime, somehow in between, in transition. Nevertheless, her handling of these liminal people and spaces is not at all formulaic; she deals sensitively with each character’s predicament.

Given our time zone differences between the West Coast and Hong Kong, we conducted our conversation over e-mail.

Kartika Review: Swimming in Hong Kong made me reconsider what I want from a short story collection. As an avid reader of novels and memoir, I’m so conditioned now to look for overall arc, recognizable connections and characters—through lines—instead of snapshots or self-contained portraits.

But the stories in this collection kept shifting locations, subject positions, nations, chronologies. I felt unmoored, but I also began to appreciate that sense as I read. The collection made me appreciate the idea of home differently, too; so many of your characters are seeking home, so many characters live in liminal spaces.

Do you think that your moving around (peripatetic) life has helped you to inhabit the many different subject positions of the collection?

Stephanie Han: For me personally, it has, but this is only me, and I am reluctant to advocate this type of life for everyone, or to state that it brings any sort of insight into different subject positions. It was simply how I grew up, so it was all that I knew. My parents moved quite a bit in the US when I was younger, and briefly overseas, and this displacement along with my ethnic background often positioned me as an outsider. This is an important way of seeing or being as a writer—this idea of belonging everywhere and nowhere, of never quite fitting in. It led me to always think about the periphery of what is mainstream, no matter where I was, and I think that this was important. A different type of narrative develops. For some people, they move into a different place and fit right in. That has never really happened with me, but I'm okay with that now. I think what happens if you are a certain type of person—you simply learn to feel comfortable with this outsider position.

But I do not believe that moving around physically or geographically is a requirement for empathy. There are many people who move around and travel the world, by choice or circumstance, who are not particularly empathetic. Writing requires the ability to empathize. You can travel the globe and not take anything in because of your particular prism and the way you view difference. I could argue all kinds of things that result because of this way of thinking. People in leadership positions travel constantly, and it is clear that it has only reinforced certain entrenched ideas that they may hold. Anyway, there are many people who do not travel as much for financial or physical reasons, but who are able to understand the human condition because they are open to ideas and ways of being. Travel and movement can open you to different perspectives, but you have to be open to learning in the first place. Everyone is different.

KR: As a follow-up, I was thinking about questions of “writing the other” that seem to come up so often (and sometimes not enough) in publishing. So I was wondering if you had to conduct any special research or use “sensitivity readers” for any of the stories, like the title story. I believe so strongly in the power of fiction to build and create empathy, and yet I wonder where all of that fits in with discussions about the writing of “others’” experiences. Do you think it’s just always case-dependent?

SH: I conducted no special research. The story was inspired by those relayed to me by people who found themselves in similar situations of cross-cultural meetings, and my own personal experiences, and simply imagining how such encounters unfold. Again, much of this is down to empathy and how this affects the construction of the literary characters as they appear on the page. I did have an African American writer read the story, but I didn't request a read for any kind of specific idea as there may have been other aspects, beyond portrayal of a specific character's racial identity, that I wanted feedback on. Since it was more than a decade ago, I can’t recall anything really specific about this.

Also, note that people assume, for example, that because I am Asian, I am able to write a non-English speaking Chinese working class male like Froggy [in the title story]. I find this interesting as it prioritizes the difference of race above similarities of class, geography, education, immigration pattern, nationality, age, and gender—all of which, more or less, I might have in common with Ruth [from the same story]. So there's that. We share our humanity, and this is what we might attempt to see in each other. The details of how this humanity unfolds in the work is what we work on and correct. It’s down to empathy.

KR: So maybe we could say that your research involves several kinds of cross-cultural meetings, listening to others’ accounts, diving into personal experience, and a deep empathy. I really appreciate that willingness to listen to and engage these kinds of experiences.

I always wonder about how writers decide on the order of their short story collections—I envision it as something like making a mixtape, if that simile’s not completely outdated! How did you decide the order of this book?

SH: It was ordered differently, and there was another story that was in the collection that the publishers decided not to include. I understand the reasons why, and I do think that the collection as a whole reads better as a result. I like the way that they ordered the stories, and I myself, have challenges ordering stories or poems. I was grateful and glad that they ordered the collection!

KR: We’re in an age where short story collections are harder to publish—and indeed, you talk about this collection as a work of almost two decades in the making! You’ve got a poetry collection, but as a writer, what draws you to writing short stories? And what do you think the short story collection offers readers that other popular genres (novel, memoir) might not?

SH: I wrote short stories because I was interested in narrative. Storytelling. And short stories are easier to manage, obviously, than a longer work. I also came through the academic tube of the MFA, and short stories are the backbone of fiction workshops. I was also a teacher for many years. So there's a personal history for me with short stories that is rooted in a rather pragmatic and unromantic notion of why I read them. Short stories work with short attention spans. I taught many young people. Short stories work in certain classrooms because of this. You are delivered to another place emotionally and geographically and/or historically for a brief period of time. Pop in. Pop out. It’s fun. And sometimes that’s all we need. A little pick-me-up. Given the rapidly dwindling attention spans we have due to our devices and online reading, I think that they will become increasingly relevant; that said, I think it is down to how people view the act of reading and text. If it becomes that people prepare themselves to read a longer work in book form, as in “Oh! I am going to read a book. This means I will read a very very long story!,” we may not see more short stories as a physical book will stand in for a Long Story Reading Experience. A lot of how and what we read is based on our ideas and expectations of what we want and expect from the act of reading. I’m sure all the book marketing people have the stats and studies on this that I do not have and thus have figured it all out.

KR: You’ve said elsewhere that you are a different reader and writer than when you began the stories in this collection. Can you say more about that?

SH: I did my PhD, so during that time I read a lot of dense, often poorly written (let’s get real, a lot of academic writing is a jargon-filled nightmare; good ideas do not necessarily translate into good writing) work. Yet, I also came to see the value in reading for a closed specific audience. When I started this collection, I was strictly a fiction reader. I began to read more non-fiction and memoir, and came to appreciate different types of writing like long form journalism. I’m also more flexible with how I read, and I read for different reasons. I don’t read everything. I know writers who do. I’m not one of them. I'm also a random reader. If you flash a book cover in front of me, I’ll say, okay, and have a go. I’m vulnerable to marketing techniques, anything marked down to $2USD in an old box, and dental office finds. I go through phases of reading different types of work. You know what I’m reading now? A Wrinkle in Time with my kid, The Da Vinci Code (missed that cultural conversation by a decade) and East, West by Salman Rushdie.

KR: You’ve also said that you are interested in helping people find their place in the world. Although teaching has seemed to fulfill that function for you, do you think that writing the collection has helped you find your place in the world?

SH: Yes, as it made me sort out the different places and phases of how I came to write and think about human behavior. Writing the collection helped me to make sense of what I observed. Deliberately crafting a narrative was, I see, my way of trying to give a story to the world as I saw it—the similarities and the differences that we share as people around the globe. The hopes and the disappointments. The mistakes we make. How we laugh. Writing helped me sort it out. There are many ways that we can understand ourselves and our world. Writing is only one way to do this.

There are also two steps, the writing of the collection and the publication of it. A lot of energy was spent trying to publish the book. If you are concerned with immediate publication, you must write of the time and a place that people understand and know, in a way that they understand and know—this is both in concrete action and metaphorically speaking. If you write of what people perceive to be something that they cannot quite imagine, particularly if you are writing literary realism, even if you are writing of the past, you will have challenges finding a place for your work. Of course, how are you to know until you write it? That’s the misery and surprise!

As for my place in the world, I think publication of the book shifted my own perspective on what I need and want from writing and life. Publishing as an older writer is much different, I think, than publishing when you are younger as my social identity was perceived in a different way than I felt myself to be by many people. I think that is the challenge that many writers who are unpublished face. I really understand and empathize with this. Writers are thinkers; they are trying to make sense of their lives and universe in a way that many people cannot see or attempt to invalidate unless the writer has a book out. But feelings should always be honored. Stories are worthy. Personal ideas matter. There is dignity in who we are and how we think. We must always respect readers and writers and the way that they are trying, in a constructive manner, to make a place in the world for their ideas and thoughts, as in the future, we may find that they speak to our hearts in unexpected ways, give voice to our desires, and say what we long to say, if only we had this courage.

KR: In a recent Kartika Review interview with Christine Lee, she talks about her “perfect reader”—do you have a perfect reader?

SH: No. No perfect reader. Imperfect readers who enjoy the stories are fine. You like one story and hate four? That’s okay. You like one. I’m okay with that! The perfect reader is about someone who understands you, who “gets” you, and who shares some intimacy of thought with you. I think we are different selves with different kinds of people, and that there are only certain sides we share and expose to each other with any ease. And this is across all of our relationships, beyond our readers. It’s a question of reach, and what we seek from another, a reader, anyone. So I don’t think I have a perfect reader.

KR: Although so many of the characters in your stories are in liminal places, what or where is home for you as a writer, as a reader? In what kinds of books, genres, do you feel most at home? What communities feel most like home to you?

SH: I’m at home in different places, and in terms of reading patterns, I don’t have any. I read pretty much anything. I’m very random. I’m thinking I will try to be more systematic, and should be, but we’ll see how that project goes. We read for different reasons throughout the course of our lives (or at least I have), so I am not necessarily looking to read about a particular experience that I have had, that I might share, but sometimes enjoy reading about people and places that are completely foreign to what or who I am. It’s like company—sometimes you like being around people who are just like you are, and sometimes you enjoy time with someone who comes from another world and learn about what the person thinks about life. Asian American literature is important to me as it gave me a way of seeing and helped me to understand my own social navigation in the US, as did, actually, much literature by American writers of color. I like reading perspectives from people who are often on the periphery of their particular society as I think that we can glean much about the world from how it deals with people on the margins. These are often people who bear witness in unusual ways.

KR: How has it felt to finally have this collection out in the world, after what you’ve described as “pounds” of rejection slips? And what are you working on next?

SH: Relief. I’m glad it’s out there. I have two manuscripts now ready to go: a literary criticism manuscript on the aesthetics of the 21st century Asian American novel, “The Art of Asian America,” and the other is a book of poetry, “Passing in the Middle Kingdom” (semi-finalist for a publication prize) mostly set in Mui Wo, Lantau, Hong Kong. I just completed co-writing a novel with Paula Young Lee (author of Deer Hunting in Paris). It was a lot of fun writing with someone else, and we’re excited about the project. Stay tuned!